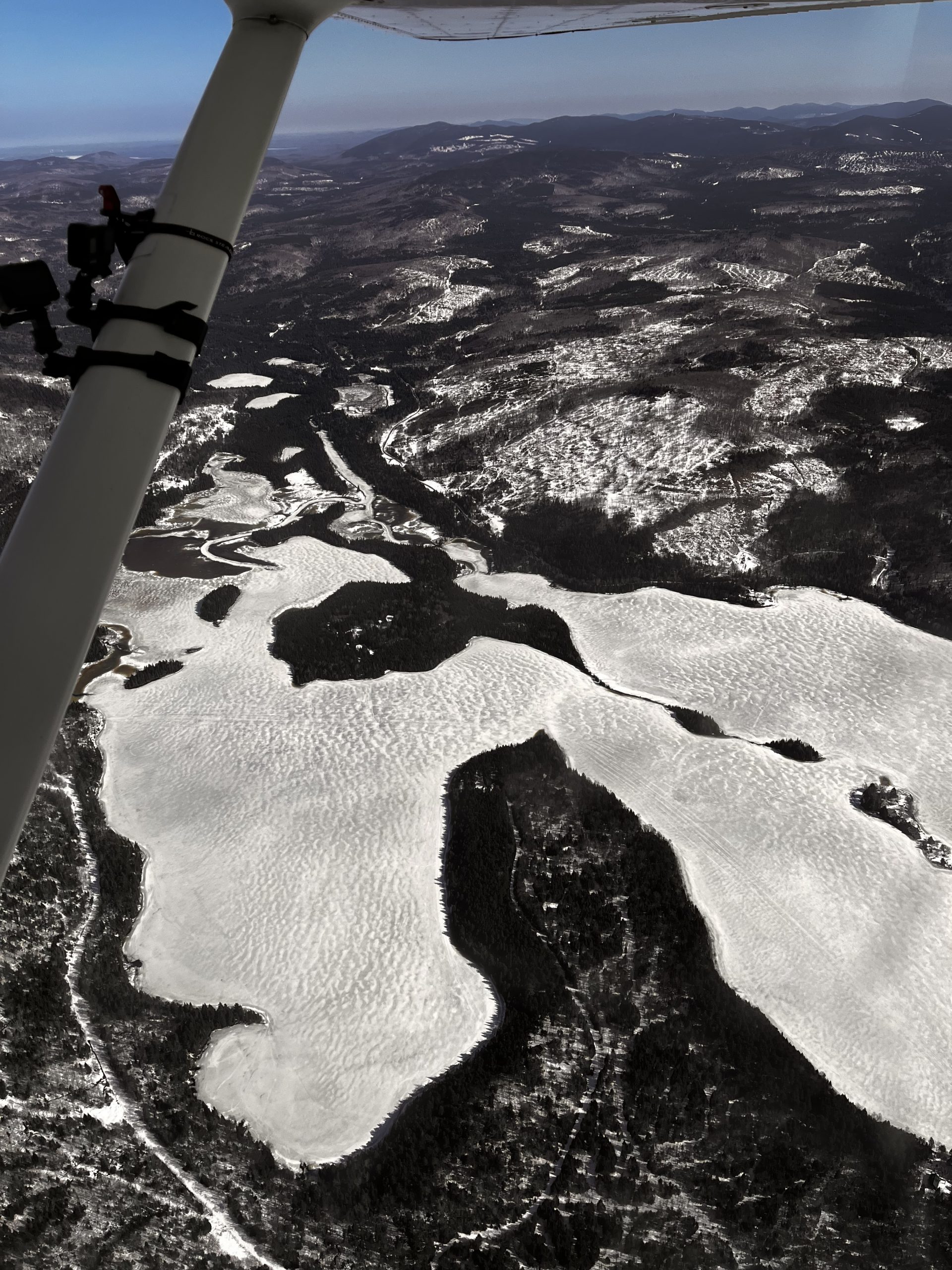

Flying over Lake Winnipesaukee looking for loons stranded by ice on the lake. Photo by Harry Vogel.

The Issue

Life as a loon is filled with challenges. One of the most deadly? Mistaking a small piece of lead fishing tackle for food. For loons, ingesting lead is almost always a death sentence, with most dying within just 2 to 4 weeks.

Or you might have to deal with shoreline development, which takes away valuable habitat and forces you to find a new place to live. Loons build their nests on the shorelines or islands of lakes and ponds; the same areas people often develop for homes or recreation.

And if lead or development doesn’t get you, there’s still climate change. High temperatures can stress loons while they’re nesting, and heavy rains can flood their nests entirely.

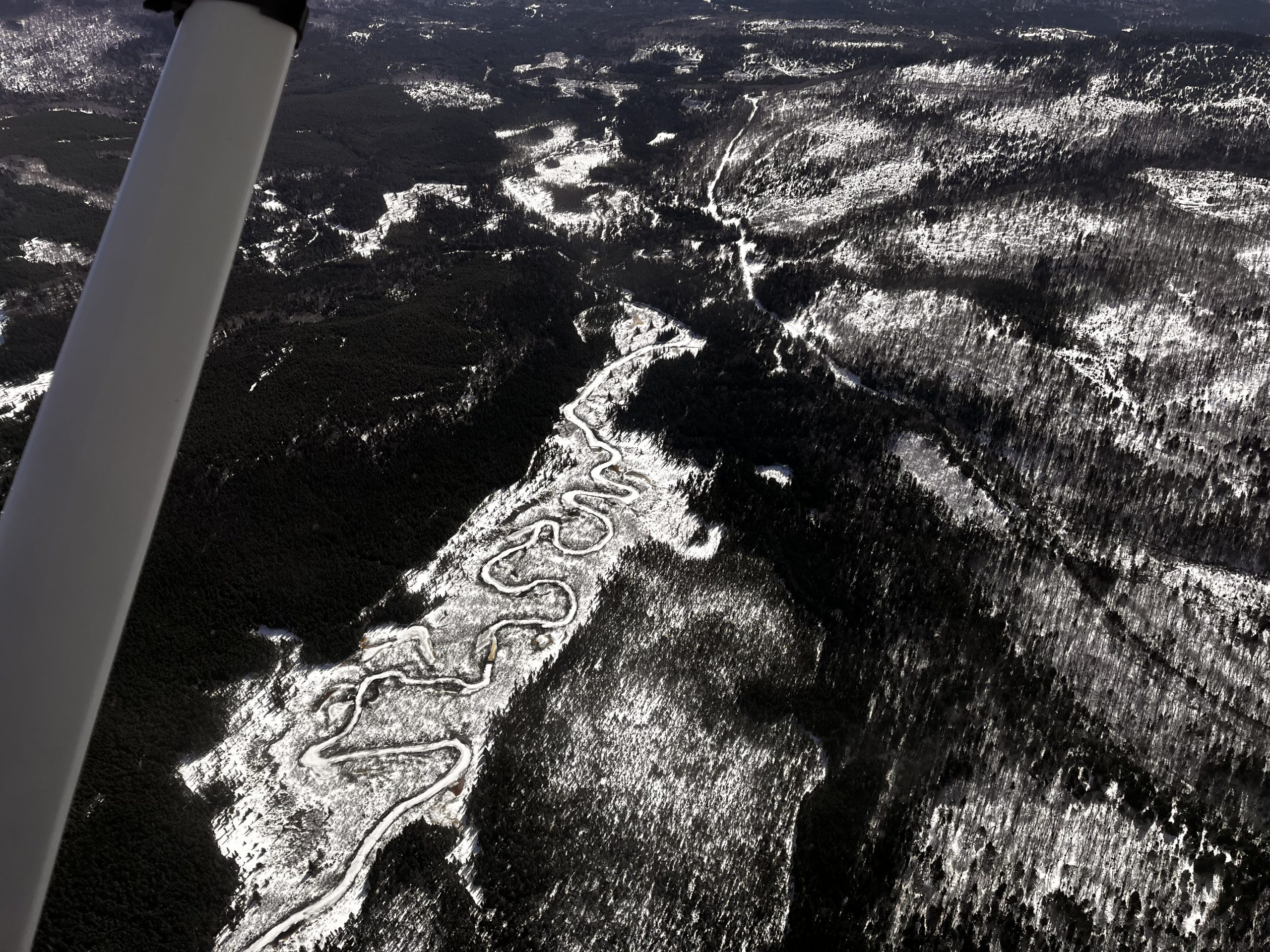

And if you make it through all of that, winter comes along and strands you in the middle of a partially frozen lake. Loons take off by running across the surface of the water while flapping their wings to create lift. Unfortunately, they cannot do this on land. Their legs are positioned too far back on their bodies, making them unable to walk on solid surfaces. As ice forms, the water runway for a loon shrinks. If it becomes too small, a loon can become stranded, unable to take off.

Flying over a frozen river looking for stranded loons. Loons need open water in order to be able to take off since their legs are not meant for walking on solid ground. Photo by Harry Vogel.

The Mission

This LightHawk flight allowed the Loon Preservation Committee to survey most of Lake Winnipesaukee in central New Hampshire for stranded Common Loons. Approximately 35,000 acres of lake surface were covered during this flight, and fortunately, no loons were found to be stranded.

Harry Vogel of the Loon Preservation Committee said:

“Finding and rescuing loons is most difficult on large lakes like Winnipesaukee, where much of the lake is not visible from shore and cannot be easily accessed due to stretches of thin ice. Flying over these areas is the only way to locate loons in need of rescue in these remote sections. The information gained during this flight will allow us to focus our efforts on the remaining areas of open water. Thank you, LightHawk, for helping us fulfill this vital part of our mission to help loons!”

Thank you to Volunteer Pilot Mike McNamara for donating his time and skills for this flight, helping to protect our fellow flyers.

Looking at a frozen lake searching for loons stranded by ice. Doing this work by air allows the Loon Preservation Committee to cover more than 35,000 acres of lakes and ice in a short amount of time. Photo by Harry Vogel.

Volunteer pilot Mike McNamara with a member of the Loon Preservation Committee in front of his Beechcraft Bonanza. Photo by Harry Vogel.